This article is an excerpt from “Handbook for Cantors” (3rd ed.). You can find more information about this title at the end of the article.

You will occasionally need to introduce new material to the assembly before the liturgy begins. Specific details of how this should be done, and how frequently, should be decided by those in charge of music after consulting priests and liturgists.

You should write out and perhaps commit to memory what you are going to say to introduce this music to the assembly. Speaking without a prepared text usually leads to rambling, but you don’t want to be seen as reading the text, either. Use it for reference. Be concise, and always have the text in front of you—just in case.

Speak clearly and distinctly. If you are nervous, you will probably speak too quickly or too quietly. Fight these inclinations. Believe that what you have to say is important, and convey that feeling to the assembly. Speak deliberately.

Your ability to use a microphone well is important. Practice beforehand, without the assembly present, to find the right distance from which to speak and to sing. Generally, this is between 2 and 12 inches from the microphone, but will vary according to the type of microphone, the volume at which it is set, and the acoustics of the church, and the resonance of your voice. If you have a very big voice, you may need to back off a mic, or moderate the sound of your voice, but you should still use the microphone. The best placement of the microphone is straight in front of your mouth or slightly below your mouth and angled upward toward it.

If you find that the microphone does not pick up your voice well enough from two inches away, do not move in any closer to increase the volume. This can jumble diction and cause certain consonants to pop, compounding the problem. Instead, use your ability to project. The mic will only amplify what you are putting into it. All the aspects of singing technique explored later in this book—breathing, phonation, resonance and diction—are your responsibility.

When you are preparing to introduce or review music with the assembly before a liturgy, the piece itself and your method of introduction will help you determine what to say. For a short refrain it may be enough to have the instrumentalist(s) play the refrain, to sing it yourself, and then to have the assembly repeat it. You might say something like this;

“Good morning. (Pause for a response.) Today and in the coming weeks we will be singing a refrain that may be new to some of you. It can be found in… on page…. Please follow along as I sing through it, and then repeat after me.” After the assembly sings, you might conclude with a statement of how or when the refrain will be used. Conclude with a simple “thank you.”

If the piece is longer or more complex, you might begin by reading the text aloud while the assembly follows along, or by inviting them to read aloud with you. This is also a good way to highlight the text and to get people involved in its content. Don’t teach the assembly a lengthy hymn by reading every stanza—but do read a few. If you love the words and handle them well, your delight will be catching.

How would you read this text before an assembly? Try reading it aloud to yourself.

Love divine, all loves excelling,

Joy of heav’n, to earth come down!

Fix in us your humble dwelling,

All your faithful mercies crown.

Jesus, source of all compassion,

Love unbounded, love all pure;

Visit us with your salvation,

Let your love in us endure.

Come, Almighty, to deliver,

Let us all your life receive;

Suddenly return and never,

Nevermore your temples leave.

You we would be always blessing,

Serve you as your hosts above,

Pray, and praise you without ceasing,

Glory in your precious love.

Finish, then, your new creation,

Pure and spotless, gracious Lord.

Let us see your great salvation

Perfectly in you restored.

Changed from glory into glory,

Till in heav’n we take our place,

Till we sing before the Almighty,

Lost in wonder, love and praise.

This text by Charles Wesley comes from his 1747 collection, Redemption Hymns. Reading hymns together this way can help people to embrace texts and to think of hymns in their entirety.

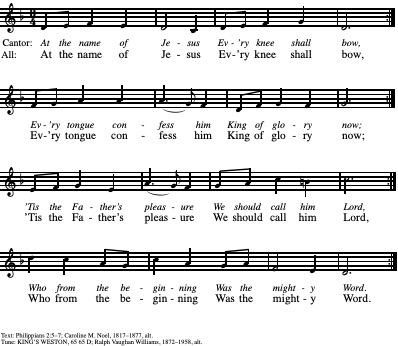

A wonderful way to teach hymns or longer refrains is a method known as “lining out.” A piece is executed continuously, one phrase at a time. Each phrase is sung by the cantor and repeated immediately by the assembly. In the following example, the cantor sings the hymn four measures at a time, with the people immediately repeating each phrase.

The stanza may then be sung in its entirety by all.

There are many ways to introduce or review music with the assembly. What is essential is that the language is clear and hospitable, that the introduction is carefully executed, and that you, the cantor, believe in what you are doing and asking the assembly to do. Make every effort not to condescend (“After I sing for you, please try to repeat the refrain!”), to entertain (“You’ll really love this one!”), or to chastise (You’re not singing!”)

You should hope for a whole-hearted response, but do not be disappointed, if the response is weak. Some people are slow to respond or fear making a mistake with something new. Others have their own good reasons for which they cannot or will not participate. People should not be judged harshly for this, nor should you blame yourself. Be consistent and take the long view. At the very least, all members of the assembly have heard the new material so it will not be unfamiliar when it comes up in the liturgy.

Sound liturgical practice suggests that once a parish has found and learned music of quality, at least some of it should be used throughout a season, or over a number of weeks of Ordinary Time. Those pieces that are used in Advent, for example, might be used throughout the Advent, and year after year. A piece used only once a year (at the washing of the feet, for example) should be used each year for a number of years. This continuity, when the music and texts are worthy, shows respect for the assembly and for the liturgy. Often, music ministers (and even other liturgical ministers) tire of a piece long before the assembly. This is because liturgical ministers have much greater exposure to the music through continued practice and the multiplication of liturgical celebrations. Try to approach familiar music in fresh, new ways each time it is used.

Handbook for Cantors (3rd ed.)

Diana Kodner Gokce

For three decades, Diana Kodner Gökçe’s Handbook for Cantors has been a gold standard for singers seeking to grow in their skills as musicians and ministers. This book presents a thorough outline of the overall ministry of the cantor—from a deeper understanding of the theology and vocation of the ministry to an examination of the practical nuts and bolts of gesture, vocal technique, and music theory.

In this third edition, Diana has significantly expanded the content to embrace not only the cantor but also the formation and skill-building of those other singing ministers too often overlooked: the priest and the deacon. This edition, in addition to expanded sections on gesture, liturgical flow, teaching music to the assembly, and the singing of psalmody, devotes an entire chapter to the chants of the priest and deacon. It includes a user-friendly approach to chanting the gospels, the formulas for chanting presbyteral prayers, an overview of some of the important chants for Holy Week, and much more. This is a comprehensive resource on singing the liturgy that no cantor or music minister should be without.

Diana Kodner Gokce

Diana is the author of Handbook for Cantors, 3rd edition(GIA Publications, Inc.). She has taught liturgical music at Loyola University and worked as a music minister in numerous Chicagoland parishes including Holy Name Cathedral. She is currently Liturgical Music Coordinator at The Frances Xavier Warde School.

Recent Comments