This post originally appeared on GIA’s “Sing, Amen!” blog in July, 2019.

I saw a post awhile back on a pastoral musicians’ forum that caught my eye. Music directors were responding to a question posed by a colleague about how much English versus Spanish there should be in a bilingual liturgy. Several responded, rather matter-of-factly, that the obvious answer is that it should be “50-50” — that is, equal parts English and Spanish. This got me thinking…

What makes a liturgy bilingual?

I’ve attended, prepared, or ministered at dozens, possibly hundreds of bilingual liturgies over the years, including outside of eucharist. One thing that struck me was that the most successful and memorable celebrations, at least in my mind, were not necessarily “equal parts” Spanish and English. In fact, they didn’t even carry with them a sense of quantitative measure or ratio, but simply “felt” right.

Perhaps this aspiration toward balance should be a question of “what does it feel like in prayer” more so than “what does it look like on paper.”

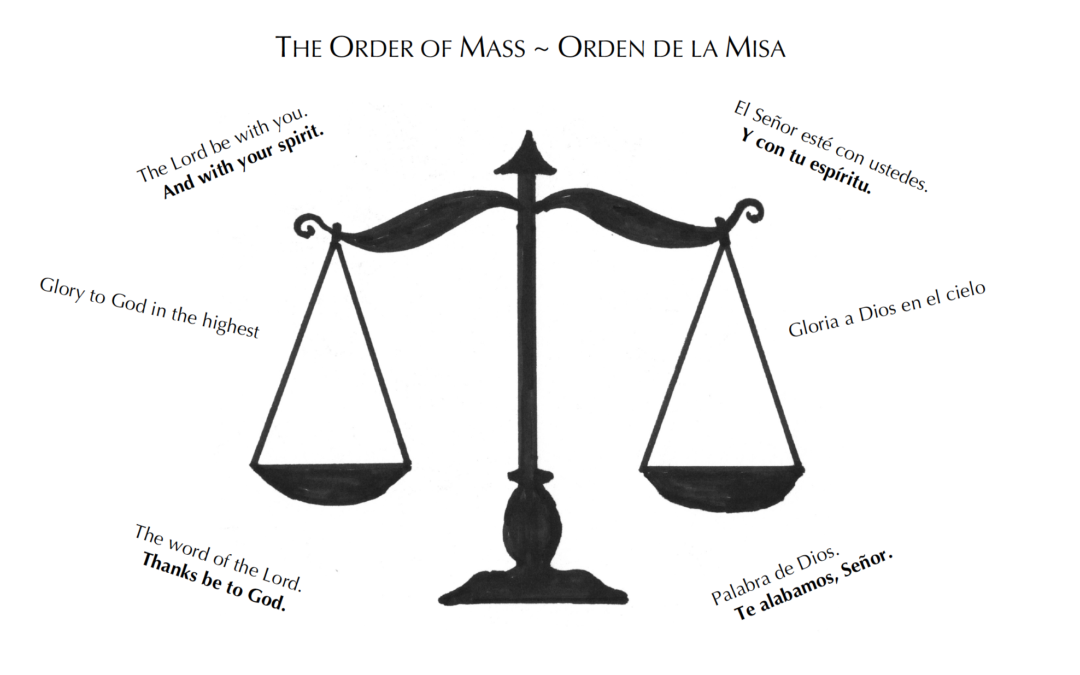

From my perspective both as a pew prayer-er and as a liturgy preparer, a bilingual mass cannot be measured in terms of percentage or quantity of texts at play, nor should it. Merely “dividing up” the liturgy to meet an arbitrary benchmark demotes the ritual to the level of a commodity, like something to be parceled off or “distributed” at the discretion of those who wield such power (the image of casting lots comes to mind). To put an artificial quantifier on the “degree of bilingualness” as the desired measure in itself misses the point. I would caution against framing our sacred mysteries in such simplistic terms.

On the contrary, I’d suggest that a bilingual mass is any in which a good faith effort is made to draw the communities at hand into the sacred mysteries by virtue of not just the language employed, but the experience in real time — via the visuals, sincerity and warmth of expression, the sounds, melody, harmony, instrumentation, rhythms, tempo, vocal style and delivery, etc. These all play a part in making one feel at home in prayer. In essence, we should be talking about facilitating a bicultural experience of prayer, not merely a linguistic fulfilling of the rite’s texts and rubrics.

Variation in Application

A bilingual mass might include (but is not limited to), mass texts and readings in varying languages, a homily skillfully rendered in a way that is seamlessly woven through intertwining narratives, music selections that are both bilingual and monolingual, musical arrangements and playing that touch the heart beyond lyrics, and visual elements such as worship aids or projection that play a practical role while lending a sensory counterweight to aural elements. Above all, a successful bilingual mass exudes a profound level of hospitality at every corner.

For some communities, a bilingual mass might see some of the spoken mass texts and preaching done bilingually, but the music entirely in Spanish. In other communities, you might find the spoken texts mostly in Spanish, but the music more bilingual-minded, even including English-only songs. Still other communities might incorporate some different blend of linguistic treatment as their norm. In communities with immigrant populations, the primary language of the community may be Spanish, but the presence of younger generations may introduce some openness to English throughout. Conversely, the desire among Latinos to want to connect with their heritage, including its “sound,” may drive English-speaking Latinos (even non-Spanish-speaking ones) to attend a mass that is Spanish-leaning in text and/or character.

Recall that the church already gifts us with vocabulary that transcends culture. The words “Alleluia” and “Amen,” preserved and handed down from their Hebrew origins, are inherently multicultural to begin with. Additionally, creative use of the original Latin (or sometimes Greek) language of our Roman rite in bilingual liturgies can also be a unifying means amidst our diversity.

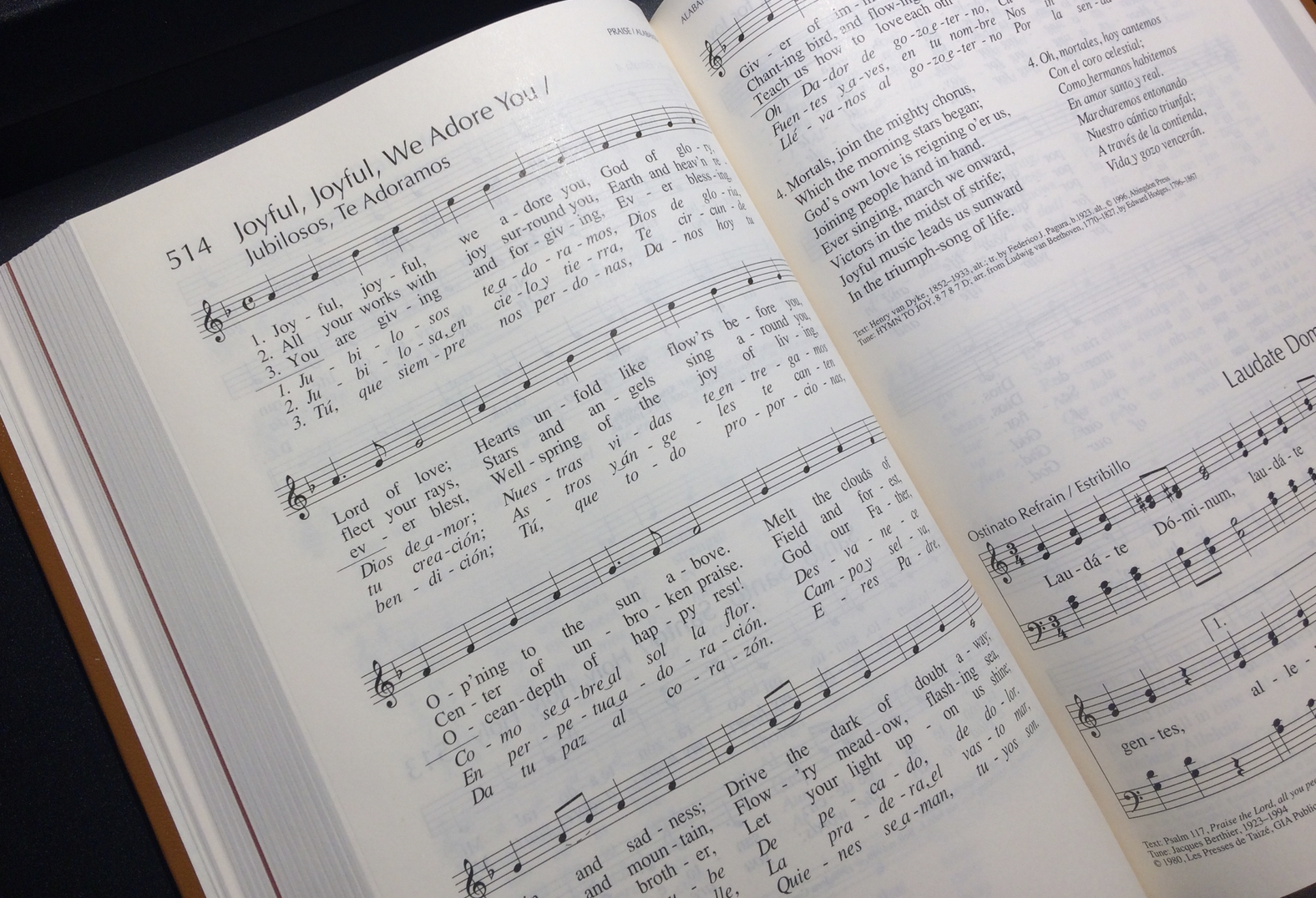

Attention to Context

Context is also a factor. Attuned to the pastoral judgment in the document Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship, certain types of musical pieces and/or linguistic treatments might work better in some celebrations than in others. In a diocesan-level liturgy, for example, where the use of strophic hymns might be normally expected, singing some of those hymns’ stanzas in Spanish might be effective — that is, for “the actual community gathered to celebrate in a particular place at a particular time” (STL, 130). Especially since there now exists good, poetic translations of English-language hymns (thanks, in great part, to our protestant brothers and sisters), inclusion of such a translated hymn could be meaningful and appropriate to either language group. A tune like “Hymn to Joy” comes to mind, whose melody is recognized across English-speaking and Latin America. This same piece or treatment, however, might not be as applicable for a Sunday liturgy at a parish where hymnody is seldom used or whose communal expectation is for more recently-composed Spanish or bilingual selections.

Music planners must also be attentive to the linguistic treatment of the mass ordinary (Kyrie, Gloria, Alleluia, Sanctus, etc.) and responsorial psalm as central to the experience of bicultural prayer.

All Bilingual, All the Time?

An important piece of advice is not to presume that just because a celebration is labeled bilingual, all of the music selections must therefore be bilingual, too. Bear in mind that the bilingual repertoire published in the last few decades serves a valuable purpose, but these compositions are meant to supplement, not supplant, the vast treasury of sacred music each culture has to offer. An overall design to the “flow” of language elements, whether monolingual or bilingual, is more important to the effectiveness of the prayer than is a de facto application of newly-composed bilingual music.

Bilingual liturgies could and should include a variety of genres and instrumentations, from classical to chant to folkloric and contemporary. A myriad of styles and musical forms exists within both the English-language and Spanish-language repertoire. These are to be explored and applied with the understanding that music speaks in a way that words alone cannot. The power of music on the ears of the faithful to uplift and transport them to a place of “at home” is difficult to define but cannot be denied. When extrapolated in creative ways, this thinking could invite a polyphonic motet in Spanish alongside a huapango in English! An open mind to this reality counters the misinformed but oft-prevalent thinking among well-intentioned planners that Hispanic music must always be mariachi style.

Key Resources

Many of these observations may resonate with your own experience or approach. Or not. The premises upon which these observations are based could be vastly different from what you see as your reality. That’s the nature of this ministry. We’re all still discovering, from the trenches on up through the hierarchy. Note that the U.S. Bishops now offer Guidelines for a Multilingual Celebration of Mass on their website. These are generally accepted as good starting points by liturgy planners, but, in the absence of official mandate, cannot viewed as definitive (nor should they be, given the ever-evolving nature of multicultural worship and perils of a one-size-fits-all approach). Of the little academic work that has been done in this field, special mention should be given to the resource Liturgy in a Culturally Diverse Community: A Guide by Rev. Mark Francis (published by the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions), the successor to his earlier, pioneering Multicultural Celebrations: A Guide. This was the first resource in the U.S. to really frame the issues and offer practical solutions, laying the groundwork for practitioners such as you and me.

In closing, I contend that a bilingual liturgy is one that is planned and executed with good intentions, and that has the net effect of welcome. The point is not to subject the participants to some kind of forced, awkward linguistic handshake, but rather that the unity gained by partaking of another’s expression of prayer far surpasses that which is lost by giving up the momentary comfort of one’s native tongue.

¡Que cantemos Amén! Let the church sing Amen!

Peter Kolar

GIA Publications

Peter is the Editor for Spanish and Bilingual Resources at GIA Publications. He is an accomplished composer and pianist known for his creative use of both classical and Latin-American musical forms. Peter holds a masters degree in music composition from Northwestern University and sits on the board of directors for the Southwest Liturgical Conference. He resides in El Paso, TX, where he is the Director of the Diocesan Choir.

Recent Comments