This post originally appeared on GIA’s “Sing, Amen!” blog in September, 2019.

This is one of the questions most of us have, whether or not we studied the organ in college, privately, or are just interested in how it all works. I happen to be married to someone who sees all those knobs and buttons as a delightful opportunity to experiment. (Kind of like playing with LEGOs.) I, however, see all the knobs and buttons and I promptly go out for coffee while he figures out the organ and how to register it. When we were playing duet concerts we would walk in to a new church to start registering our pieces and he would sit down and joyfully get started. I saw that as my cue to tiptoe ever so quietly away and slink back an hour or two later. (Most of the time he wasn’t even aware that I had left.) Over the years I have learned to be less intimidated by the process, and even to be more daring and experimental, but it doesn’t come naturally. My goal here is to give you enough information to answer some basic questions, and to encourage you to read more in-depth information if you want to learn more about the organ. Most organbuilders have good, helpful information on their sites, and as usual, Google is a great place to start on your search.

The American Guild of Organists has videos on how to register the organ, and there is other information out there if you search for Organ Registration, but let’s start with some really great questions and subjects. If you have any additional questions, or think I’ve missed anything, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

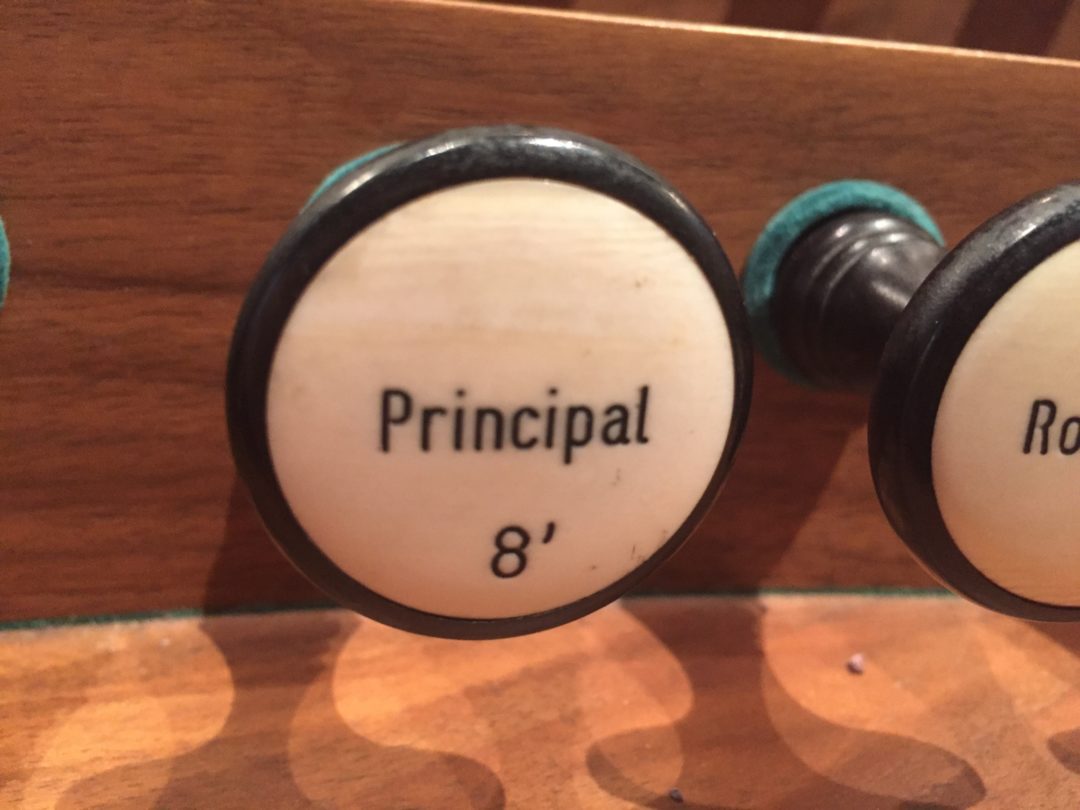

What’s with the numbers? (8 and 4 and 2 and please don’t mess with the fractions just now.) Organ stop knobs have numbers on them, such as Principal 8′, Octave 4′, Doublette 2′, Oboe 8′, etc, to let you know at what pitch level the pipe will sound. An 8′ stop tells you that the lowest note on the keyboard, a C, plays a pipe that is 8′ long. From that 8′ long pipe the ascending pipes get smaller as you play up the keyboard. Any 8′ stop you choose on an organ will sound at the pitch that corresponds to the piano keyboard. There are, however, times when the length of the pipe is not what I just described. Stopped flutes are another example, as they start at 4′ length rather than 8′, but sound at the same pitch as an 8′ stop. Here is an explanation of how that works:

“Stopped flutes, (Bourdon, Gedeckt, Lieblich Gedeckt, Stopped Diapason, Flute d’ Amour) can be made of wood or metal. The stopper is inserted into the top of the pipe and forces the air column to return down the length of the pipe to create a distance twice as long as the physical length of the pipe.” (For more information on flute stops in general, visit the site this quote came from, Patrick J. Murphy, Organbuilders.)

A 4′ stop will sound an octave higher than the 8′, and thus a 2′ will sound two octaves above the piano pitch. Therefore, a 16′ pipe will sound an octave below, so the lowest C plays from a pipe that is 16′ long. Combining different pitch levels, along with different combinations of pipes (flutes, reeds, principals), will produce a fuller sound than a piano, more like an orchestra, where multiple instruments blend together. It also is an artificial way to produce more of the octaves found in the harmonic series.

Swell vs. Great vs. Choir. Each keyboard has a different name. Let’s get started with the easy one, the pedalboard. It’s always called the pedalboard, and it’s always in the same place! Organs have anywhere from one to five manual keyboards, and they usually go in a certain order. The first one is the Great manual, called so because it used to be the main stand-alone organ, centuries ago, before organs were all put together into one console. Before that practical invention, churches would have more than one organ, such as the Great, for loud sounds, and a smaller, more portable chamber organ to accompany soloists or the choir. Once somebody got the brilliant idea to put all the keyboards together in one console, it saved the organist a lot of running around, and also enabled more keyboards to be added, with more divisions (basically, more sets of pipes).

When there are two keyboards, the second manual will always be above the Great, and it is called the Swell. The Swell is usually enclosed in a chamber with shutters you can open and close with your foot (affecting how loud the pipes sound in the room), using a pedal that looks much like a car’s accelerator pedal. When there are three keyboards, the third manual is usually called the Choir, and will be placed below the Great, and usually is also enclosed in a chamber (sometimes that manual is called a Positiv).

These are the most common manuals organbuilders use, and they are generally used in that order unless the organ is historically reproducing something from France or Germany, but you don’t need to know that at this point.

Basically, the Great manual stops will be the loudest, used for full organ and thus for hymn registrations and repertoire that calls for more sound. The Swell will have a range of sounds from a smaller, lighter version of the Great manual to including more stops with color and bite, like the reed stops. The Choir manual can have a range of colors and sounds and frequently will include stops that are suitable for accompanying the choir, (usually Swell and Choir are mixed together for choir accompaniments) as well as more interesting solo stops.

I hope this brief tutorial will begin to explain some of the mysteries of organ sounds and registration, and that you will keep reading!

Marilyn Biery

GIA Publications

Marilyn Biery is an organist, conductor, composer, hymn writer, and ASCAPlus award winner. One of her interests is the research and encouragement of new American organ music. She has written numerous articles about the subject, appearing in The American Organist and The Diapason. Marilyn holds Bachelor and Master of Music degrees in organ performance from Northwestern University, and the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in organ from the University of Minnesota.

Recent Comments